Giant Shells in Peru

Original

Article: "Giant Shells in Peru's Andes" by Enrique Raul Pando Castro

( Email: jethro1@LatinMail.com )

Originianl article which could be found on George Sangiologlu's site does

not seem to exist at this time. (http://www.geocities.com/~sangioul/ )

|

Discussions

on these findings by Conch-L members:

Visit the Conch-L Archives |

|

April 21, 2001: Dear friends,

Please enjoy the photos and more information, at: http://www.geocities.com/~sangioul/help.html

"Site address no longer valid" Best regards.

|

|

April 21, 2001: Hello Conch-L, A month ago,

George Sangiouloglou posted a piece about a discovery of giant fossil

"oysters" high in the Andes Mountains in Peru. Recently our

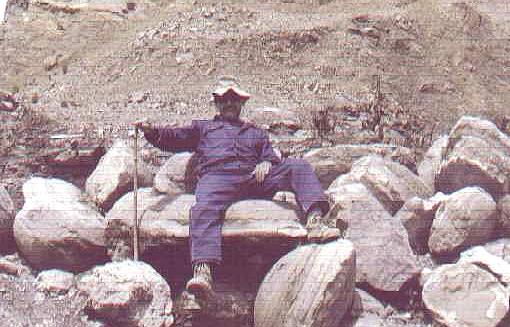

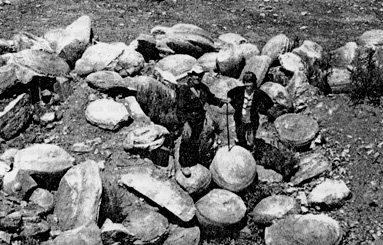

local shell club printed a picture of the find in the club http://members.home.net/paulcyp/GIANTSHL.JPG See image below Regards, |

|

|

April 21, 2001: Wow! Now those are oysters! Thanks for posting it, Paul. Scott |

|

April 21, 2001: Can anyone confirm

that these are truly fossils, and not just odd-shaped rocks that look

like "oysters?" Actually, just

out of view of the camera were foot-long fossil lemon wedges and neolithic

pottery gallon buckets of cocktail sauce. |

|

April 21, 2001: Andrew Vik |

|

April 21, 2001: I believe that

these shells are giant brachiopods. James M. Cheshire |

|

April 22, 2001: One should always

be skeptical in regards to heresay information. The lack of thought

leads to people sending known urban legends and bogus virus alerts to

others. In the case of the "giant oysters." it Bill Frank |

|

April 24, 2001: |

|

April 22, 2001: James, the thought crossed my mind, first becuse the growth lines seems to be too simetrical for a bivalve. And then, there are two photos, in Sangiouloglou's site, the 6th and the last, and they seem to depict the posterior side of brachiopods, not the dorsal side of bivalves. But pictures aren't that clear... Paulino |

|

April 22, 2001: Paulino: Wouldn't brachiopods

of that size be a greater discovery than giant oysters? Andrew V. |

|

April 22, 2001: We have about

1500 species of fossil brachs in our collection ...have sudied them

from all ages and all locations ...if those are brachs then we will

EAT them .... joe |

|

April 22, 2001: OK. Now you've

done it! Everyone knows that there are no bi-valves in the Andes. And

everyone except my mother knows there are no brachiopods at that elevation.

Well, what does that leave??? Of course!!! You have discovered the eggs

of Flying Pigs. They lay them in the Andean Summer. Art |

|

April 22, 2001: Dear Listers, Thus far, Art's construct is the first to break the plausibility barrier (at least among biotic explanations). Harry |

|

April 22, 2001: Dear George,I looked at the interesting photograhs of the "giant shells from Peru". I have seen almost the same concretions in the Jura exposed at the coast of Cap Griz Nez in northern France. Here the beach is full with con I think I only have a diapositive of them, so I can't sent you a photograph. Martin C. Cadee, The Netherlands |

|

April 23, 2001: They look like concretions to me as well. Plus, they are not really that big. The two people in the photo are midgets. G. Thomas Watters,

PhD |

|

April 23, 2001: If the structures are indeed biogenic and not concretions (hard to tell from the photos), then they are almost certainly inoceramid bivalves. I have seen inoceramids of about that size from the Cretaceous Pierre Shale in Colorado. Inoceramids are traditionally considered close relatives of Isognomon, Pteria, etc. and range from the Permian to the upper (but apparently not uppermost) Cretaceous. However, Paul Johnston and coauthors have recently suggested that they represent a distinctive extinct subclass, related to the Paleozoic "cryptodonts" like Praecardia, Slava, etc. They typically occur in dark shales (which seemed plausible from the photos). The hinges are edentulous, with numerous ligament pits like Isognomon. The shells often have broad concentric ribbing. The ligament is somewhat unusual. The outer shell layer consists of large calcite prisms that are distinctive in the sediment even after the shell has crumbled away. Inoceramids and their kin may have been chemosymbiotic. A specimen with possible traces of gill supports suggests a somewhat peculiar anatomy. George's web page mentions Plagiostoma gigantissima as an apparent guess by the discoverer. This is a European Jurassic limid (file clam), much smaller than these forms, and lacks the concentric sculpture of these specimens. The largest known brachiopod is indeed much smaller than these. Dr. David Campbell |

|

April 24, 2001: The structures are almost surely concretions and certainly not inoceramids. Although inoceramids have all the features David Campbell discussed, the large members of the family are all extremely flat forms ; ie, they could never the degree of inflation shown in the pictures. Cheers, Peter

Harries |

|

April 27, 2001: They are not

fossils. They are most likely calcareous concretions from what biostratigraphers

call "sedimentary condensed sections"; I have been able to

see these usually giant concretions embedded in dark shales in most

geologic sections of the Cretacic/ Tertiary age boundary in Eastern

Venezuela where geologic correlations to find oil reservoirs are usually

done; the shales - and not the concretions- usually contain a lot of

deep water fossil remains, such as forams, nanoplankton and mollusks,

sometimes it is possible to find large, flat inoceramids which are bioindicators

for age and basin depth correlation of the stratigraphic unit. |

|

September 03, 2003 Hello |

If you would

like to add your ideas and comments on these giants,

Please write to me: Avril Bourquin

Please put Giant Shells in Peru on the subject line.

Thanks!

|

OR

|