|

Spondylus,

Strombus, and Conus: National

Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History,

|

|

Este artículo también esta disponible en español (spanish). Sin embargo, la página suplementaria aún no esta traducida. Nuestras disculpas por la lentitud en poner esta traducción en línea y gracias por su paciencia. (17 de setiembre de 2002). |

|

Introduction: The use of the sea-like sources of resources for subsistence have been considered by the Andean people of South American from times immemorial. Inside specialized literature, the study of the different remains that show the use and exploitation of the resources of the sea is denominated as “marine subsistence”. This way, these items understood as both vertebrates and spineless remains such as: marine mammals, fish, birds, crustacean, algae, and of course, molluscs. These resources continue to be exploded actively at the present time, maintaining industries and communities of traditional fishing (in ports denominated caletas) all along of Peruvian coast. However, some species of marine molluscs were appreciated, not only for their meat, but also for their size and their attractive forms and colors. These shells served as a basic matter to make personal decorations and artifacts for rites. In Andean area of Peru, approximately 4,500 years ago there emerged the first big temples that were organized to agricultural societies that counted among their main products; the potato (Solanum tuberosum), corn (Zea mays), yucca (Manihot esculenta), cotton (Gossypium barbadense), among others. Also, the temples produced the first artistic images that expressed their beliefs, captured in fabrics, gourds, figulinas of mud, objects worked in bone or lithic engravings. All this happened before the appearance of the pottery for what the archaeologists denominate to this period Late Preceramic or Archaic. In this context, the first indications of the presence of the Spondylus princeps are detected, one of the big molluscs of the Andean ritual that lives in warm waters of the Ecuadorian coast toward the north, arriving until the Gulf of California. At the moment two species are food: Spondylus princeps and Spondylus calcifer and they are distributed in the whole tropical sea of the Pacific, that is to say from Punta Mal Pelo at Tumbes (Mogollón 1999) until the Gulf of California. They are of free life, with occasional fixation of mall area in its shell to the rocks or dead shells. In the area of California the plungers report it to depths of 25 until the 90 m., with few specimens at 15 m.. 10,000 individual colonies or more was viewed on sandy surfaces to 43 m depths. The fact that these big populations are detected can be due to that the fact that fishermen don't reach these depths (batimetría) in their search for the food (Skoglund Carol and David K. Mulliner 1996: 96). |

|

The Ecosystem of the Coast: The coast of Peru is conformed by the Peruvian Province and the Panamian Province which are according to the marine currents that bath their coast: the Peruvian Current (Humboldt) and the Ecuadorian Tropical Current respectively. Due to it, the marine fauna varies sensibly in each one of the regions of molluscs. The oceanographic factors that impact in to the differentiation of the species of molluscs that are located in the adjacent marine coast they are:

The Current Tropical Ecuadorian of warm waters reaches temperatures that fluctuate approximately between 24 and 29 °C. The waters of the Peruvian Current (Humboltd) fluctuate between 14 and 18 °C. There are four types of beaches: swamp (“manglar”), sandy, sandy / stony and stony. The molluscs can live in the areas of fluctuation of the tides, reef of the waves or in the marine funds (infralitoral).

|

|

Ornamental and Ritual Molluscs: In the Central Andean archaeological sites (Perú), there is a group of molluscs documented in context of no-subsistence that attracted the attention of pre-Columbian societies from the beginnings of the civilization in America for their singularity, rarity and beauty. In chronological order of appearance these they are:

The last two species are clearly identified here for the first time in Peru’s archaeology. They have their habitat in the Panamanian Province, and for this reason they arrived in the Peruvian Andes from the coasts of Ecuador (Although the species Malea ringens, Strombus peruvianus, Conus fergusoni, Pleuroploca princeps and Fusinus panamensis are distributed throughoput the tropical sea of the Peruvian north). They became indispensable in religious and funeral rituals, and they constituted ornamental elements, distinction and prestige between shamanes and warriors, reinforcing the symbolic power of these members of the social elite. Between these big tropical molluscs, the Spondylus princeps played a main role, being very considered and an object of intense traffic until Inca times (Rostworowski 1977; 1999). |

|

Antecedents: The use of the shells of tropical molluscs for the first residents of the region of the Ecuador (North’s Andes) goes back to Las Vegas culture, 10,000 - 6,600 B.P. The contexts and species that appears are:

(Stothert 1990).

Later, the ritual use of the big molluscs Spondylus princeps, Strombus peruvianus and Strombus galeatus related to the water’s cult in this region and are located in the remains of the Valdivia culture toward the 3,200 B.C. (Marcos 1995:99; Marcos 2002). Marcos thinks that several natural factors created this relationship between the Spondylus and the rain. They are:

(Marcos 2002:15, 16) |

|

The Presence in the Central Andean: The early presence of the Spondylus princeps in the Central Andean, like traffic testimony at long distance, has been reported for monumental sites of the Late Preceramic Period or Archaic in Peru like:

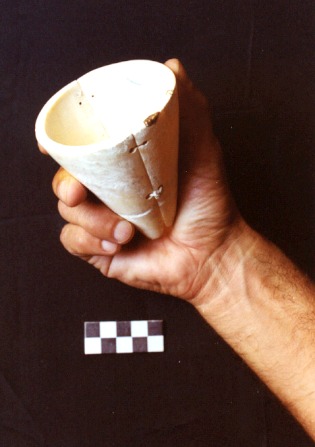

From the examination of the objects, contexts and dates we can say that the presence of the Spondylus princeps in sites of the Central Andes can be averaged in 2,500 B.C. We mean, approximately 700 years after of Valdivia culture in the Ecuadorian region. On the other hand, in this first stage it is generally founded in contexts of fillers in some big ceremonial centers, like small worked objects (earring or circular bead that were been used to manufacture necklaces, also called “chaquiras”) in tiny quantities. This is important, because it points out that the Spondylus was inserted in this Andean region when several monumental traditions of religious architecture were developed and began influencing each other (Burger 1993). The Spondylus intervened as a secondary element in rites of constructions and used as distinction ornaments and prestige items by a small elite, but it didn't arrive to be represented in images corresponding to remains of this period. Neither is it documented of the specímens presence or whole valves, which indicates that the objects that arrived to this part of the Andes were probably already worked before they came. This situation stays until the appearance of the pottery in the region (2,000-1,800 B.C.). As example we have the circular, cubic and lengthened beads of Spondylus that appeared during the works in “U” shaped temple of Garagay (Rimac valley), a monumental complex that was occupied among 1,500-600 B.C. (Ravines et al. 1982: 161). Two of them came from a well of offerings located in the atrium in the right arm of the complex. Later, in Cupisnique

culture (1,300-600 B.C.) from the Formative period

Discoveries of devices

worked in Spondylus in a tomb in Cerro Blanco (Cajamarca): There

are square badges and beads that show bigger sophistication and care in

their elaboration, one of the badges is decorated with a face of Chavin’s

features. |

|

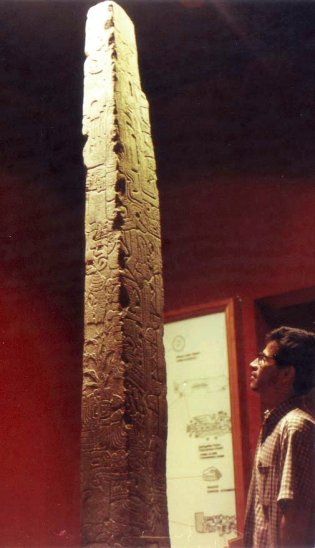

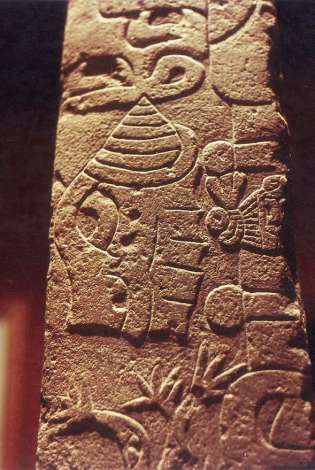

In Chavín of Huántar (1,200-400 B.C.) it appears as:

| |

|